Co Mat Vien- The "CIA'' of Nguyen Dynasty

Origin and Purpose

The “Lê Văn Khôi” Incident

Lê Văn Khôi was the adopted son of Lê Văn Duyệt, a loyal and highly respected official under Emperor Gia Long, who was also the father of Emperor Minh Mạng.

Lê Văn Duyệt was an exceptional mandarin, honored with two rare imperial privileges: “entering the court without bowing” (nhập triều bất bái) and “executing before reporting” (tiền trảm hậu tấu) — distinctions almost never granted in Vietnam’s feudal history.

Though loyal to Emperor Gia Long, Lê Văn Duyệt deeply disagreed with Minh Mạng, the successor. He had even opposed Minh Mạng’s succession during Gia Long’s reign. Despite several attempts, Minh Mạng could not remove him from power, as Duyệt had immense influence and the late emperor’s full trust.

In 1832, shortly after Duyệt’s death — by then he had served as Governor-General of the South for over a decade — Emperor Minh Mạng ordered his aide Bạch Xuân Nguyên to investigate him. Upon arriving in the South, Bạch Xuân Nguyên compiled an extensive report accusing Duyệt of corruption and abuse of power.

In truth, Lê Văn Duyệt had greatly contributed to the South’s prosperity. He directed the construction of the Vĩnh Tế Canal (linking An Giang and Kiên Giang), developed infrastructure, and defended the region from invasions by Chân Lạp (modern-day Cambodia).

Beloved by the people, Duyệt still appeared as a threat to the imperial court because of his immense authority and open disagreements with the emperor.

After his death, many of his relatives and aides were punished, and some were executed. These harsh actions sparked the Lê Văn Khôi Rebellion, led by his adopted son, who already resented the imperial court. The uprising caused serious unrest, forcing the Nguyễn Dynasty to send large military forces to restore order in the South.

Ironically, the bond between Lê Văn Duyệt and Lê Văn Khôi began under unusual circumstances. In 1819, while Duyệt commanded imperial troops to suppress a rebellion in Thanh Bình (modern-day Ninh Bình), he captured Khôi — the leader of that very uprising. Impressed by his courage, Duyệt spared Khôi’s life. In return, Khôi pledged loyalty to him, later becoming his adopted son and trusted aide.

Today, Lê Văn Duyệt’s private residence, a gift from Emperor Gia Long himself, still stands at 20 Phú Mộng Street, right at the entrance to the lane leading to Ancient Huế.

The Establishment of the Cơ Mật Institute

After the Lê Văn Khôi Rebellion, Emperor Minh Mạng realized the need for a specialized agency dedicated to intelligence and national security. He founded the Cơ Mật Institute—literally meaning “top secret”—to collect, analyze, and deliver strategic information vital to the royal court and the nation.

This institute was led by four senior ministers, each ranked Chánh Tam Phẩm (Third Rank or higher), representing four key royal departments:

- Văn Minh Palace (Civil Administration)

- Võ Hiển Palace (Military Affairs)

- Cần Chánh Palace (Policy and Governance)

- Đông Các Pavilion (Scholarship and Literature)

Together, they formed what was essentially the emperor’s special inner cabinet.

Within the compound, the main hall served as the workspace for these high-ranking officials. Two side wings complemented it: the right wing housed French delegates (Délégué), while the left wing later became the Economic Museum (Musée Économique).

Though the architecture remains intact, the building’s purpose has evolved. Between 1955 and 1975, the side wings served as offices for local judicial bodies of Thừa Thiên Province and Huế City, while the main hall—the original Cơ Mật Institute—functioned as a courtroom for both first-instance and appellate trials.

Today, the historical site is located at 23 Tống Duy Tân Street, in Thuận Thành Ward, at the southeastern corner within the Imperial City of Huế.

Historical Evolution of the Site

From Royal Residence to Sacred Ground

In 1802, when Emperor Gia Long ascended the throne, the Phú Xuân Citadel was dismantled. The site was then repurposed as the residence of Prince Đảm, who would later become Emperor Minh Mạng.

In 1816, after Prince Đảm was appointed Crown Prince and moved to a new residence in the eastern sector of the Imperial City, this property became the home of Prince Nguyễn Phúc Chẩn, the emperor’s younger brother.

Later, it was inherited by Nguyễn Phúc Thiện Khuê, the eldest son of Prince Chẩn.

In the 20th year of Emperor Minh Mạng’s reign (1839), the land was reclaimed by the court to construct Giác Hoàng Pagoda—a magnificent temple later listed by Emperor Thiệu Trị as one of the twenty scenic wonders of the imperial capital.

Transformation under French Colonial Rule

After Vietnam lost its sovereignty to French colonial rule, the entire structure of Giác Hoàng Pagoda was dismantled. In its place, the French administration built the Viện Cơ Mật (Secret Institute), completed in 1903.

This was where critical state affairs were discussed between the Nguyễn Dynasty and the French colonial authorities, making it one of the most politically significant sites in Huế during the early 20th century.

Architectural Design and Layout

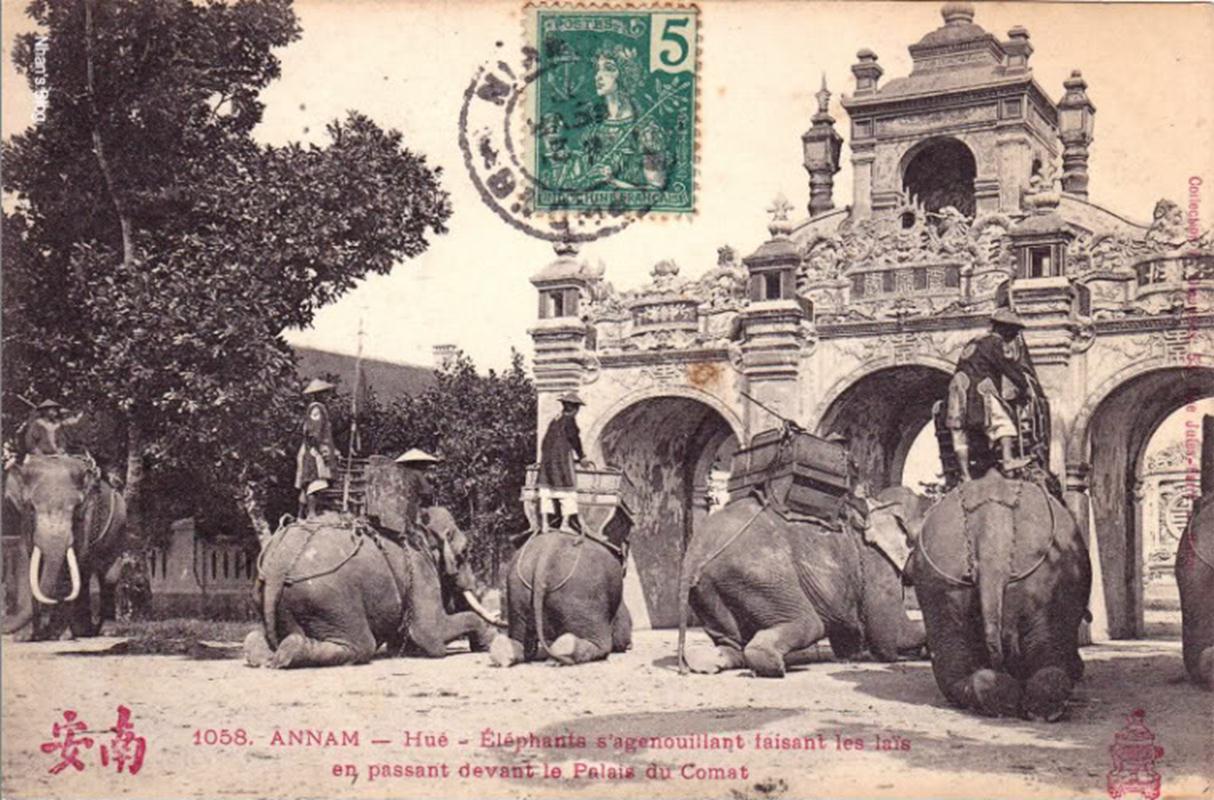

The architecture of the Viện Cơ Mật reflected Western European influences, blended subtly with traditional Vietnamese symmetry. The complex consisted of a two-story main building flanked by two side wings.

- The upper floor featured the inscription “Cơ Mật Viện” (Secret Institute) in seal script, enclosed within a circular frame above five moon-shaped doorways (nguyệt môn).

- The lower floor included seven moon-shaped doorways, complemented by three decorative screen walls and six additional moon-shaped doorways on either side.

- Each side building contained fifteen chambers with two projecting wings, forming a balanced and imposing layout.

The entire complex was surrounded by a brick wall with three main gates located at the front, left, and right sides—symbolizing authority, order, and accessibility.